MCDONOUGH, Ga. — Cutting-edge products introducing new breakthroughs in medical technology are launched every day in the U.S. healthcare market. Press releases announcing these new products are published in medical journals and generate attention and excitement in the hospital executive suite.

Unfortunately, the realm of linen distribution may seem somewhat less compelling to hospital administrators, and the notion that there may be advances in linen distribution technology may have never occurred to them.

Many years ago, the responsibility for distribution of hospital linen was the exclusive domain of the on-premises laundry (OPL). The OPL manager often supervised the entire process, from washing to delivery, to picking up soiled. However, with the gradual closure of many hospital OPLs, responsibility for linen management was assumed by department heads who had little training or experience with it.

Materials management, dietary services and environmental services (EVS) were the primary departments to take over responsibility for hospital linen, and many facilities chose to become rental customers and leave management of linen replacement and inventory to a co-operative or commercial laundry. Responsibility for getting clean linen to the end-user, however, has generally remained in the hands of the hospital.

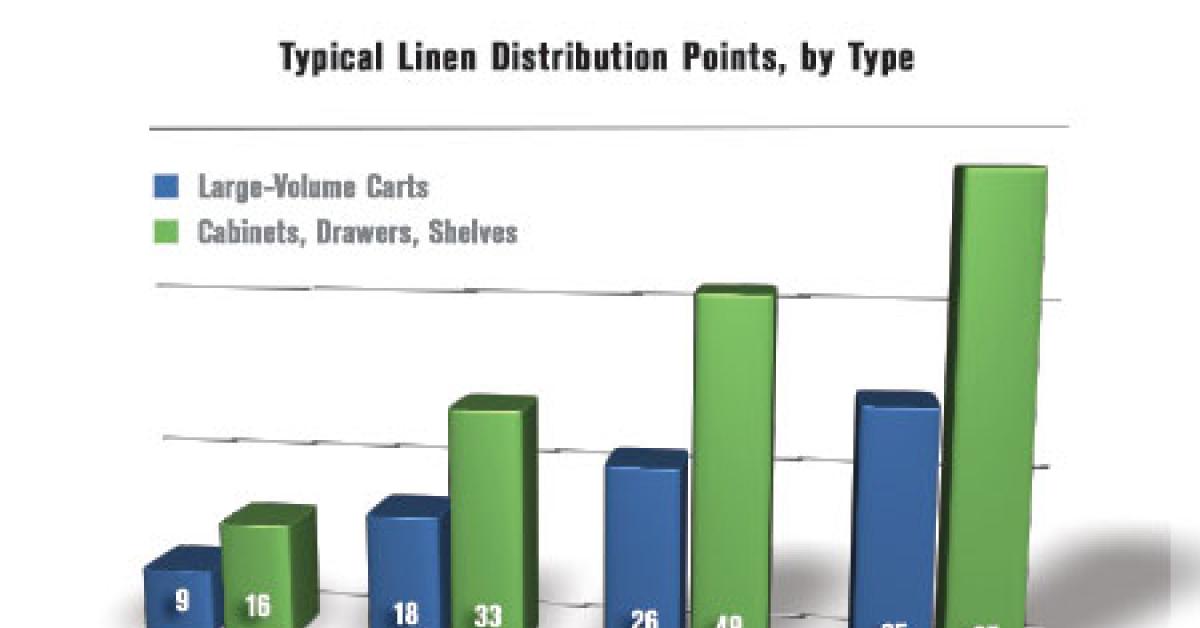

A recent study of users of Encompass Group’s ExecutorNET® linen management software program revealed that the average number of distribution locations in a hospital per 100 beds is 25. A 200-bed hospital would generally have 50 separate stocking locations; a 300-bed hospital around 75; and a 400-bed hospital could have close to 100.

Thirty-five percent of these stocking locations (about nine per 100 beds) are designated as inpatient departments, which are generally, along with the emergency department, the major linen users in the hospital where linen is stocked on carts in large volumes. The balance of the linen stocking locations are designated as outpatient, surgical, or miscellaneous (a catch-all category for locations like dietary, doctor sleep rooms, etc.), and are primarily areas where linen is stocked in smaller quantities in cabinets, drawers or small shelving units.

EXCHANGE CART, REPLENISHMENT AND REQUISITION

The traditional ways to supply linen to end-users consist primarily of these methods: exchange cart, replenishment, requisition, or a combination of the three.

In an exchange cart system, each user area is allocated two shelved carts capable of holding a 24-hour supply of linen. As one full cart is delivered to the user area, the depleted cart is returned to the linen room to be refilled.

This method, popular with larger hospitals, is usually implemented in major inpatient departments—the operating and emergency rooms—and works well in conjunction with handheld data-collection devices for linen management software systems. Major considerations are the amount of space a hospital has for cart staging and the amount of inventory required to maintain the duplicate carts.

Replenishment systems are the most common approach and are used for all categories of user departments. In this method, the linen distribution personnel take linen directly to user departments to stock carts and/or closets to a par level.

The par level may be a specific amount established formally through statistical usage analysis, based on the judgment and experience of the linen distribution person stocking the cart, or simply whatever fits on the shelf.

While there are fewer issues with the amount of stocking space and inventory, one disadvantage of a replenishment system is a diminished ability to supervise staff during the stocking activity.

In a requisition system, user departments place orders with the linen department for their linen needs on a daily/weekly basis. This method is most common in outpatient areas, clinics and medical office buildings (MOBs) that utilize small amounts of linen or have unpredictable usage patterns.

The disadvantage of the requisition system is that it relies on end-user department personnel to accurately assess their linen needs and not overorder. Overordering can easily lead to the buildup of excess linen, or “dead stock,” that pulls valuable linen product out of circulation.

OUTSOURCING

Outsourcing linen distribution to a co-op or commercial laundry processor is a trend that has been consistently increasing over the last decade. The path to the outsourcing continuum is set into motion by a hospital when it closes its OPL and becomes a rental customer of a co-op or commercial laundry.

Linen management responsibility is then assumed by EVS, materials management or dietary, as previously discussed, where linen management is not a core competency. This often leads to the hospital deferring to the external laundry to manage more and more of the hospital linen distribution process until the external laundry decides to install its own employee as the on-site linen manager. The external laundry may also eventually assume payroll responsibility for the entire linen distribution staff.

The final steps in the continuum are when the external laundry begins to build exchange carts at its processing facility for delivery to the hospital dock (and ultimately directly to the hospital floors) and picks up the soiled linen.

The disadvantage to this model is that the hospital has relinquished all control to its linen processor and is often not in a position to change vendors easily if the relationship flounders.

Check back Thursday for the conclusion!

Have a question or comment? E-mail our editor Matt Poe at [email protected].